Would legal doping change the Olympics?

The impact would be smaller—and worse—than proponents of drug-taking claim

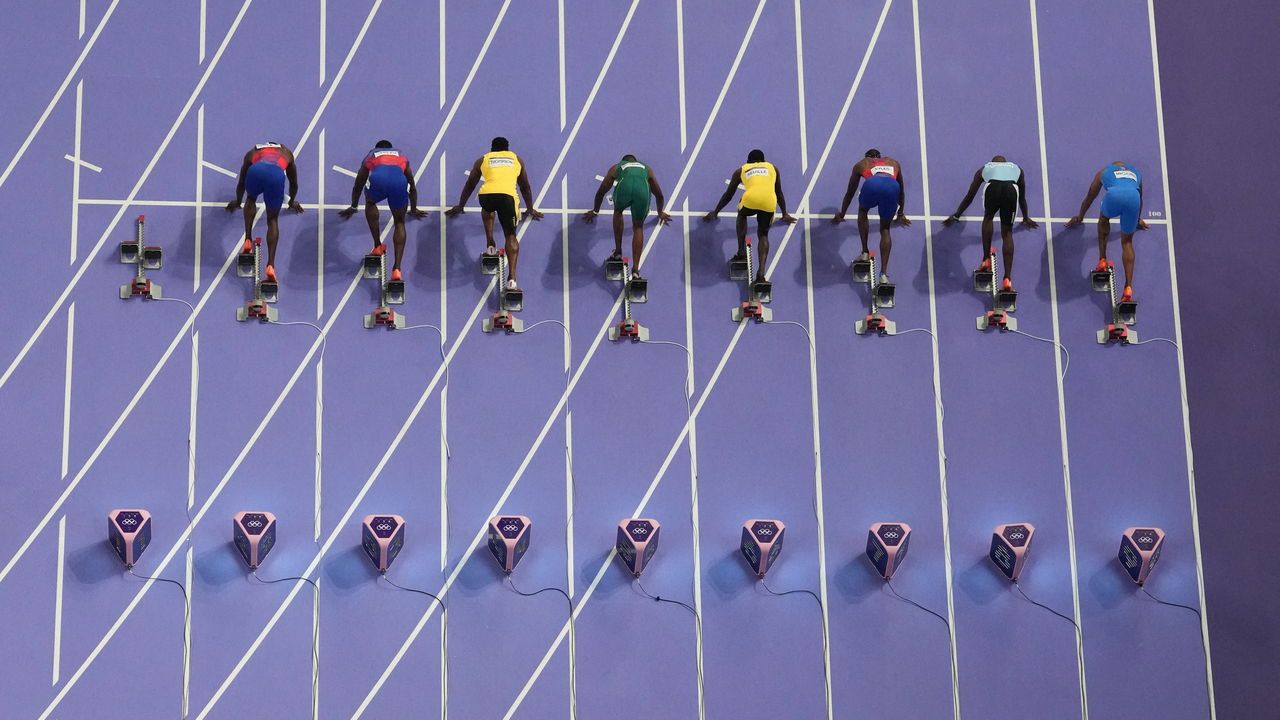

TRYING TO RID elite sport of drug cheats is an expensive and often thankless task. Competition organisers can never be sure that an event is clean: retests of samples from the Beijing and London games led to more than 100 medallists being disqualified. A small minority—including Aron D’Souza, an Australian businessman—believe it is time to lift the ban and make drug-taking a legitimate means to boost performance. Mr D’Souza plans to hold a doped competition, dubbed the Enhanced Games, in 2025. Most athletes have dismissed his plan as absurd and dangerous. But he believes that doped competitors would beat plenty of official world records. Is that true?

More from The Economist explains

Do vice-presidential picks matter?

If they have any effect on an election’s result, it is at the margins

What led to the bitter controversy over an Olympics boxing match?

A mighty punch by an Algerian boxer has revived a politically charged dispute

Is this the end of Project 2025, the plan that riled Donald Trump?

The right-wing blueprint for governing has taken centre-stage in America’s presidential campaign

Who should control Western Sahara?

France becomes the latest country to back Morocco’s claim

Who are the Druze, the victims of a deadly strike on Israel?

The religious minority has often been caught up in regional crossfire in the Middle East

Myanmar’s rapidly changing civil war, in maps and charts

Ethnic militias and pro-democracy groups are scoring victories against the governing junta